Diameter lower bound in local certification (2)

15 Apr 2021This is the second post about the certification lower bound of diameter. The first post is here. In this post I will describe the framework for the reduction from communication complexity.

The content of this post is based on Approximate Proof-Labeling Schemes by Keren Censor-Hillel, Ami Paz, and Mor Perry.

Communication complexity background

In the previous post we have been playing with the idea of transferring information from one side of the graph to the other. This is formalized by the model of (2-party) communication complexity. In this model, there are two players Alice and Bob, who are given inputs $x$ and $y$ respectively, and have to compute a function $f(x,y)$. The classic setting is that $x$ and $y$ are binary strings, and $f(x,y)$ is a bit. To compute $f(x,y)$ Alice and Bob exchange information.

The trivial technique is that one of them, say Alice, sends her whole input to Bob, and then Bob computes the function and sends the result to Alice. If $x$ and $y$ have size $t$, then this takes $\Theta(t)$ bits.

Sometimes we can do much better. For example, suppose that $f(x,y)$ is the number of 1s in $x$ + the number of 1s in $y$ modulo 2 (that is the parity of the concatenation of the inputs). Then it is possible to use only $O(1)$ bits of communication: Alice and Bob compute the parity of their own inputs without communication, and just send this one bit to the other player.

For our proof, we will need the non-deterministic variant of this model. In non-deterministic communication complexity a prover gives a certificate $s_A$ to Alice and a certificate $s_B$ Bob and it should hold that:

- on yes-instances, that is instances where $f(x,y)=1$, there exists a couple $(s_A,s_B)$ such that after communicating, Alice and Bob do output 1.

- on no-instances, that is instances where $f(x,y)=0$, there is no couple $(s_A,s_B)$ such that after communicating, Alice and Bob output 1.

The communication is measured by the number of bits in $s_A$ and $s_B$, plus the communication between Alice and Bob.

Disjointness problem

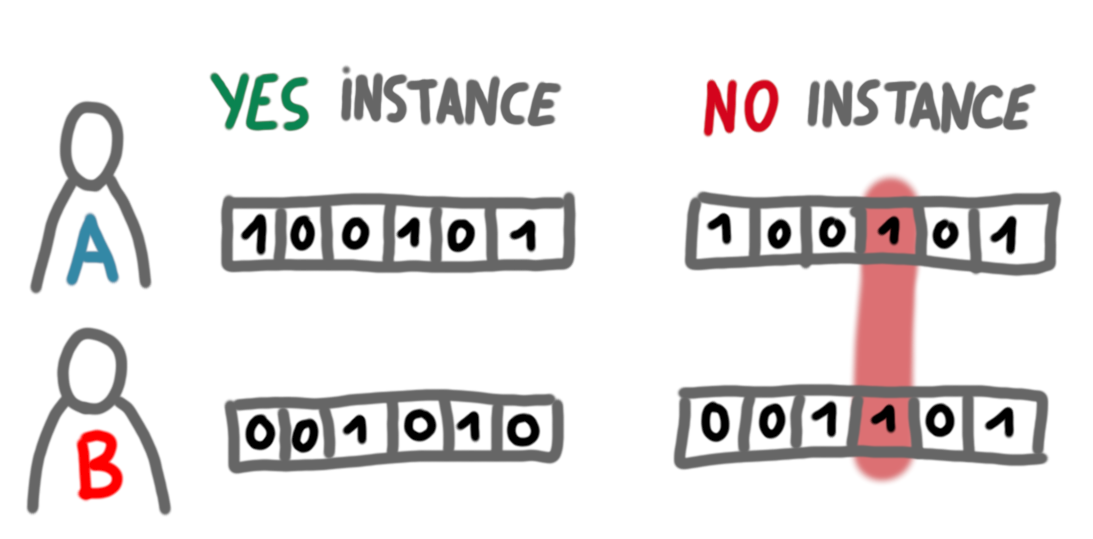

The problem we are going to use is Disjointness ($DISJ$), probably the best known problem in the field. It is defined the following way: $DISJ(x,y)=0$ if there exists a position $i$ such that $x_i=y_i=1$, and 1 otherwise. In other words Alice and Bob should accept only if the positions of the 1s in their inputs are disjoint.

A celebrated result states that the communication complexity of Disjointness, even in the non-deterministic setting, is $\Theta(t)$. That is, there is no better way to convince Alice and Bob that they have disjoint inputs than to basically write their inputs in the certificates, and let them exchange these certificates to check the consistency. That’s what we are going to use.

Just to give some more intuition, let us consider the opposite problem, $NON-DISJ$, where the yes-instances are the ones where Alice and Bob do have a position $i$ such that $x_i=y_i=1$. For this problem there is a very efficient non-deterministic protocol. For yes-instances $s_A=s_B$ is a position $i$ where $x_i=y_i=1$, and Alice and Bob can check that indeed this was a 1 in their respective inputs (and exchange the certificates to check that they were given the same position $i$). There is no way to fool the players in no-instances. This takes only $O(\log t)$ bits of communication complexity.

Framework of the reduction

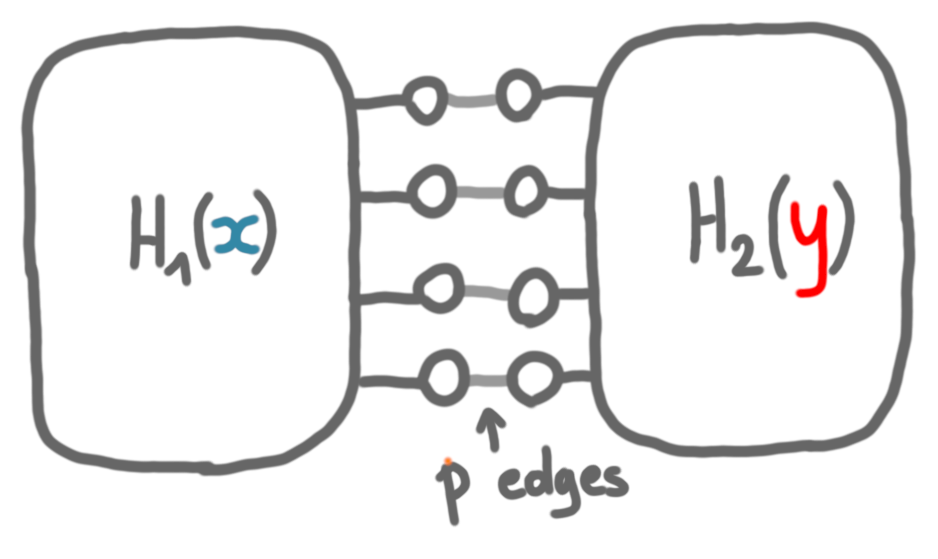

I will now describe the high-level idea of the reduction. We need to translate the Disjointness instances, which are the binary strings $x$ and $y$, into diameter instances, which are graphs. Given $x$ and $y$, we are going to consider a graph $G(x,y)$ made by connecting two graphs: $H_1$ whose structure depends only on $x$ and $H_2$ whose structure depends only on $y$. These graphs are going to be connected by a set of $p$ edges. The nodes of $H_1$ and $H_2$ to which these edges are connected are called gate nodes.

(The gate nodes are part of $H_1$ and $H_2$, they are drawn outside in the picture for convenience.)

The key point is that we will build the graphs $G(x,y)$ such that the following claim holds:

Claim: $DISJ(x,y)=TRUE$ if and only if $DIAM(G(x,y))\leq k$.

We will describe the precise structure of $G(x,y)$ in the next post. For now let’s see how the reduction works.

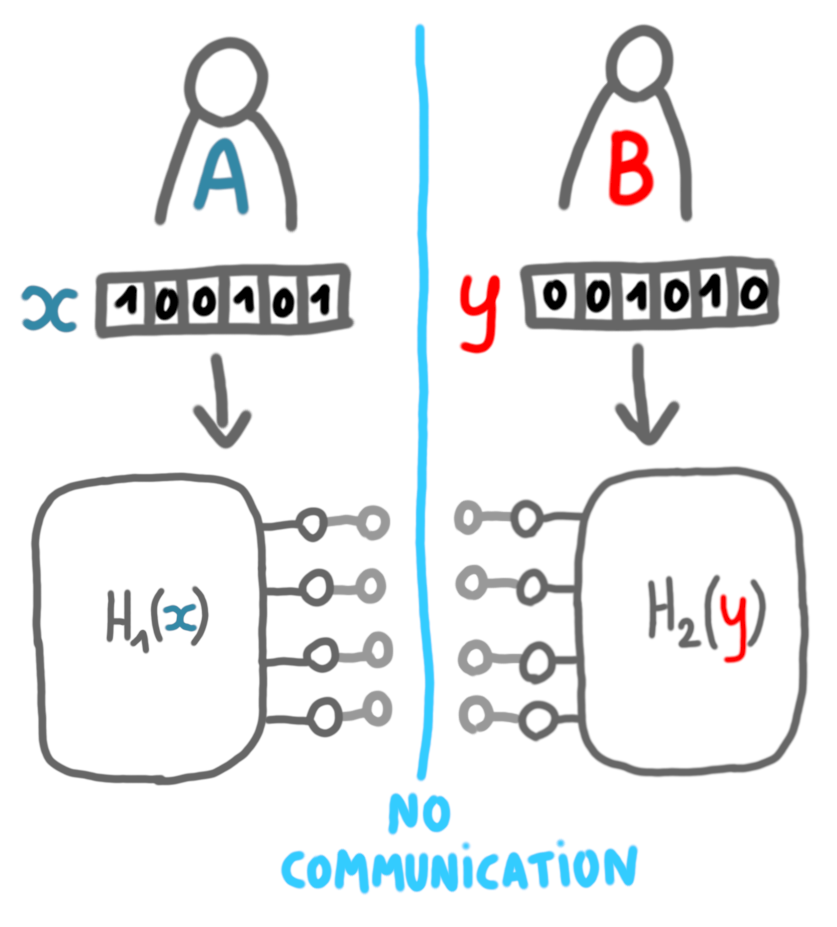

The fact that each part depends only on one of the entries means that Alice can compute $H_1(x)$ and Bob can compute $H_2(y)$, without communication. Actually they also know that there will be gate nodes on the other side, so they can also compute whose.

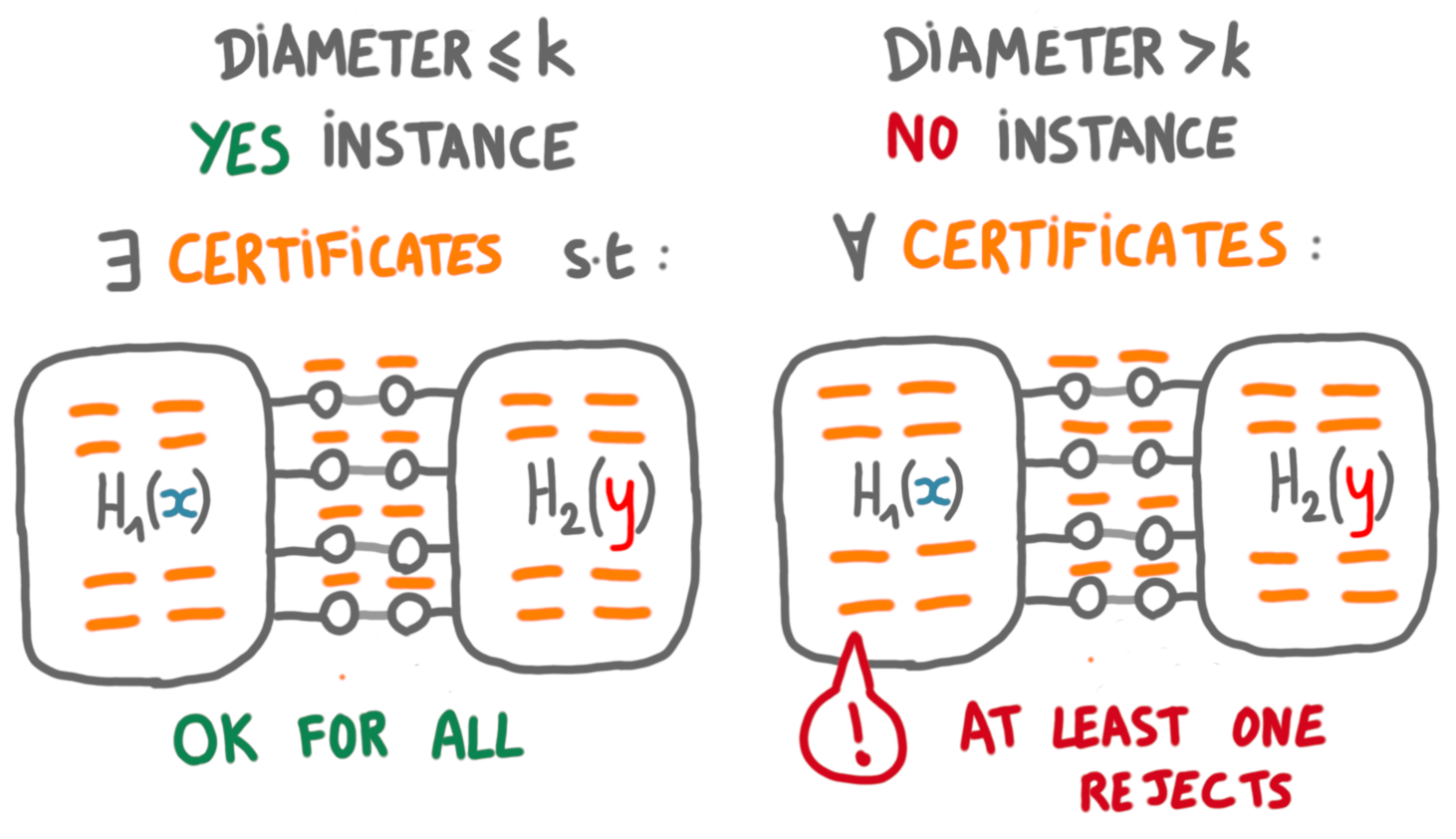

Now suppose we have a certification of diameter $\leq k$ with certificates of size $c$. Then in particular for the graphs $G(x,y)$, the usual conditions hold.

Let’s now describe the communication complexity protocol. On yes-instances, the prover will give to Alice the certificates of the nodes of the graph she has computed, and to Bob the certificates of the nodes of the graph he has computed.

Alice and Bob, when they receive the certificates, will simulate the local verifier on all the nodes of their graphs, except the gate nodes of the other player.

If in this simulation one of the nodes rejects, then they will exchange messages saying that they should reject. If all nodes accept on both side, then they will exchange messages to make sure that the prover gave them the same certificates for the gate nodes. If it is the case they both accept, otherwise they reject.

This is a correct scheme because the strings $x$ and $y$ are disjoint, if and only if $G(x,y)$ has diameter $\leq k$, if and only if there exists local certificates such that all nodes accept.

Discussion of the sizes

The size of the certificate given by the prover to Alice (resp. Bob) is basically the number of nodes of $H_1(x)$ (resp. size of $H_2(y)$) multiplied bu the size of the certificates in the local certification setting, $c$.

Let $t$ be the size of $x$ and $y$. As we will see in the next post, the function that maps $x$ to $H_1(x)$ (resp. $y$ to $H_2(y)$) is such that $H_1(x)$ and $H_2(y)$ have $\approx \sqrt{t}$ nodes.

Putting things together, thanks to the reduction we now have a non-deterministic communication protocol for Disjointess, that uses $O(\sqrt{t}*c)$ bits, for strings of size $t$. We know that this has to be in $\Omega(t)$. Thus $c$ must be of size $\Omega(\sqrt{t})$.

The size of the graph is basically $\sqrt{t}$, thus $n\approx \sqrt{t}$, thus $c$ is in $\Omega(n)$. We get our lower bound!

In the next post we will describe the construction that maps $x$ and $y$ to $H_1(x)$ and $H_2(y)$.

$\rightarrow$ Next post of the series