Rake-and-compress and 3-coloring trees

13 Nov 2020I have encountered the rake-and-compress method a couple of times recently in distributed computing, and I think it’s an idea that can be useful in different areas of algorithmics. Here’s a post about it, with an application to distributed 3-coloring of unoriented trees in $O(\log n)$ rounds.

Context

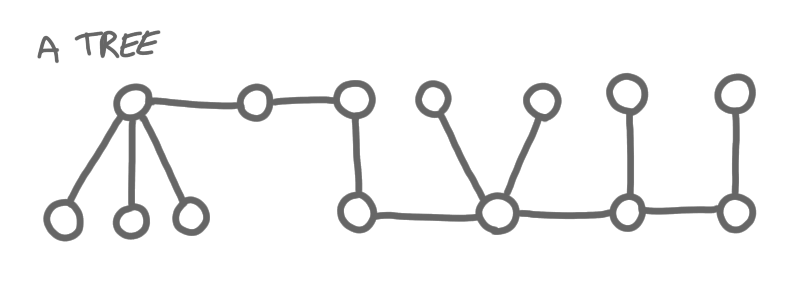

Rake-and-compress is a method to deal with trees. It is sometimes the case that you have good algorithms for special cases of trees, but that it is not clear how to deal with general trees. For example, for distributed 3-coloring, paths are easy (we have algorithms in time $O(\log^*n)$) and binary trees are also easy if we aim for $O(\log n)$ time. Rake-and-compress is a way to decompose a general tree, that helps to combine methods for special trees and methods for paths.

Rake-and-compress originates from a paper of Reif and Miller from 1989, where they used it for expression evaluation and subexpression elimination in the PRAM model. I know it from the paper Distributed recoloring by Bonamy, Ouvrard, Rabie, Suomela and Uitto, where it is used in a distributed context. The writing of this post is based on this later paper.

Rake-and-compress idea

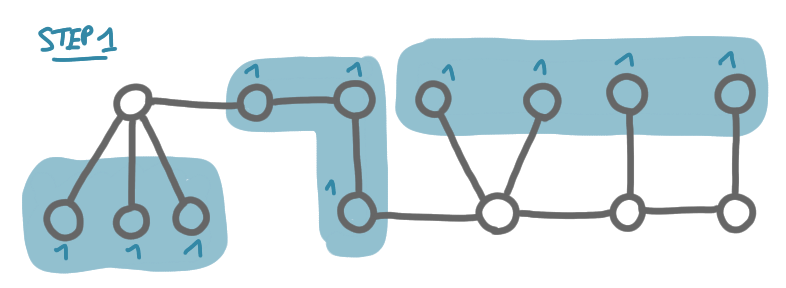

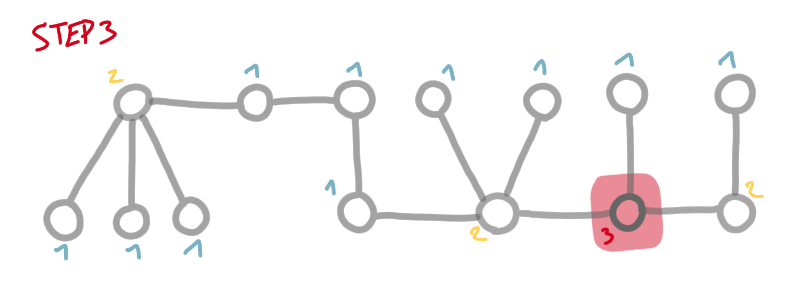

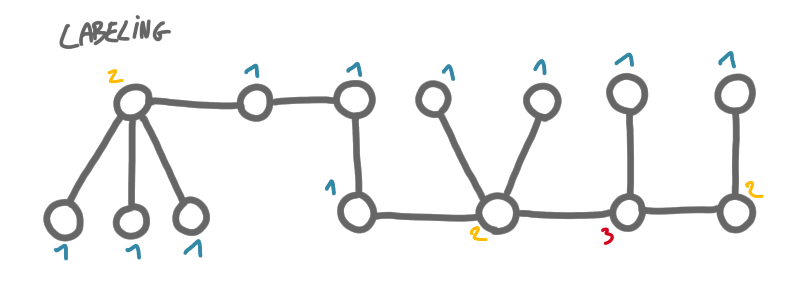

There are several variants of the rake-and-compress method, but basically it consists in doing iteratively two operations:

-

rake: remove the leaves of the tree,

-

compress: remove “long” paths in the tree (that is long paths of nodes of degree 2).

These two operations can be a bit different depending on the context. For example, in the wikipedia article about tree contraction the rake consists in keeping only one leaf per node having leaves as children, and the compress consists in replacing every path by an edge, hence keeping connectivity. (The picture above also show a rake-and-compress where the tree stays connected.)

The idea is that after a logarithmic number of rake-and-compress the tree is empty or reduced to a few nodes/edges. In the next sections, I’ll describe a concrete application of rake-and-compress.

Rake-and-compress to get a labeling

Consider the following labeling algorithm:

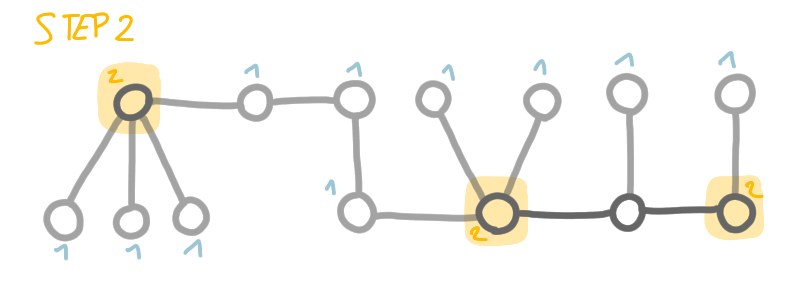

1. i = 1

2. "the forest" = the tree

3. while the forest is not empty:

a. find the leaves

b. label them i

c. find the nodes of degree 2 that belong to paths

(of nodes of degree 2) of length at least 3.

d. label them i

e. remove the nodes with label i from the forest

f. i++

4. output the labeling

The labeling we get has the property that a node has few neighbors with the same or higher label. More precisely:

- a node of label $i$ has at most 2 neighbors with labels larger or equal to $i$,

- a node of label $i$ has at most 1 neighbor with label strictly larger than $i$.

This is easy to check. Consider a node $v$ and the step $i$ when it is labeled. At that step, if $v$ is a leaf, and then it will have only one neighbor with larger label, its parent. If $v$ is in a path of degree 2 nodes, then it has at least one of its neighbors of degree 2, thus with label $i$, again the properties are satisfied.

Why $O(\log n)$ steps are sufficient.

We claim that after $O(\log n)$ loops in the labeling algorithm, the forest is empty. In other words, the labels are between 1 and some $\alpha \log n$, for some constant $\alpha$ ($\alpha=2$ is actually enough). A formal proof of this can be found in the distributed recoloring paper, but I prefer to present an intuitive proof (it is a bit heuristic, maybe slightly wrong, but hopefully meaningful).

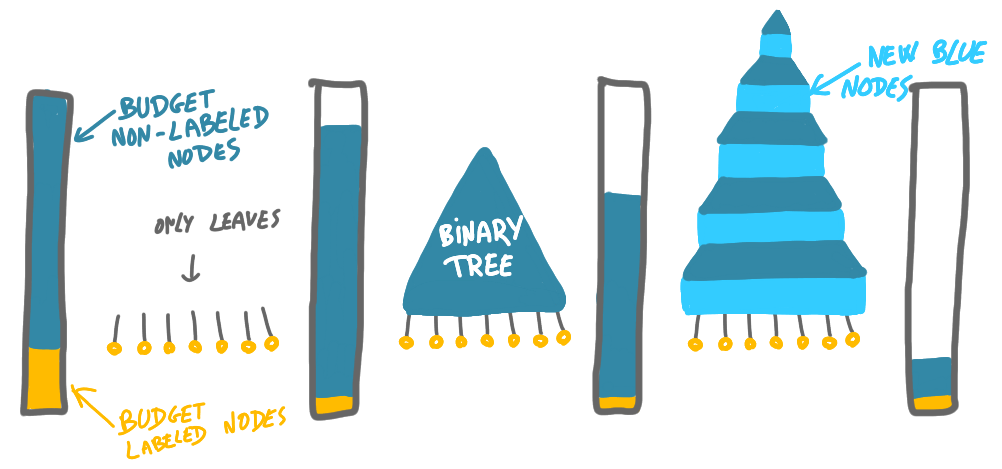

The idea, in the formal proof and in the informal one, is that at every step at least a constant fraction of the remaining nodes is labeled. This is enough to show that there are at most $O(\log n)$ steps. Suppose this is not the case. Then consider a tree of the forest at some step $i$ where strictly less than 1/6 of the nodes are labeled. Let $k$ be the size of this tree.

To prove that this is impossible, consider the following point of view. We have a budget strictly smaller than $(1/6)k$ of nodes that can be labeled (leaves or paths), and we have to build a tree of size $k$. See the picture below for illustration.

The tree must we have $(1/6)k-r$ leaves, for some $r$. Then we want to get the maximum number of non-leaf nodes, without using paths. We choose to have the smallest degree possible, with the largest amount of nodes: a complete binary tree. This gives us at most $(1/6)k-r$ nodes, thus we still have to sneak $(2/3)k+2r$ nodes in. If we replace each edge of the binary tree by a path of three edges, we do not create path of degree-2 nodes of length three or more, and we have used $2\times((1/6)k-r)=1/3-2r$ new nodes. We only have $4r$ nodes to add, $3r$ of which must be unlabeled. But there is no room for these nodes: any addition would result in a new labeled nodes.

In the following we will call $h$ the maximum label.

Using the labeling to get a 3-coloring

We now use this labeling for distributed 3-coloring unrooted trees. As said in the introduction for this problem we have a $O(\log^*n)$ algorithm for paths, and trees of $O(\log n)$ diameter are also easy in $O(\log n)$ time: just look at the full tree and 3-color it. Now for other types of trees its not that clear what to do. (Note that we are talking about unrooted trees, rooted trees have fast algorithms.)

Consider the following algorithm:

1. Compute the labeling.

2. For each label, compute indepedentely of 3-coloring

of the nodes of the paths of this label.

3. The nodes that are not in a path are given color 1.

(Now every node has a label i and a color c.)

4. For label i from h to 1:

For color c from 1 to 3:

The nodes that have label i and color c

choose a color in [1,2,3],

among the colors not already chosen

by their neighbors.

If the algorithm succeeds then it is clear that it provides a 3-coloring in time $O(\log n)$. What is left to prove is that it does not block at some point: there is never a node that has to choose a color in [1,2,3] but all the colors are already used by neighbors.

This is easy to check using the properties of the labeling. Indeed, when a node has to choose a color, only nodes of strictly larger label have chosen a color, and each node has at most one neighbor in this case. Also, a node has at most two neighbor with the same label and then no node with higher labels. Such nodes either chose after, or have already chosen a color (because of the 3-coloring of the paths we computed), thus there cannot be a conflict there either.