Certifying a perfect matching in a planar graph

06 Mar 2024(In this post I will assume familiarity with the concept of local certification. If you are curious about this, my introduction to the area is here.)

Next week, Sébastien Zeitoun will present the paper Local certification of local properties: tight bounds, trade-offs and new parameters at STACS, a joint work with Nicolas Bousquet and myself. The motivation for this paper, and our first main result is a proof that in order to locally certify that a graph is k-colorable, one basically needs to give the coloring in the certificates. But here I’d like to sketch a cute side result we have about matchings on planar graphs.

Perfect matching certification

We want to certify that the graph at hand has a perfect matching. A natural way to do that is to give to every node the identifier of the neighbor it is matched to. Every node can easily check that this is consistent. But this takes $\Theta(\log n)$ bits. Can we do better? We have some related lower bounds in the paper, indicating that probably not. But when the graph is planar, we can do it with only two bits!

Contraction and four color theorem

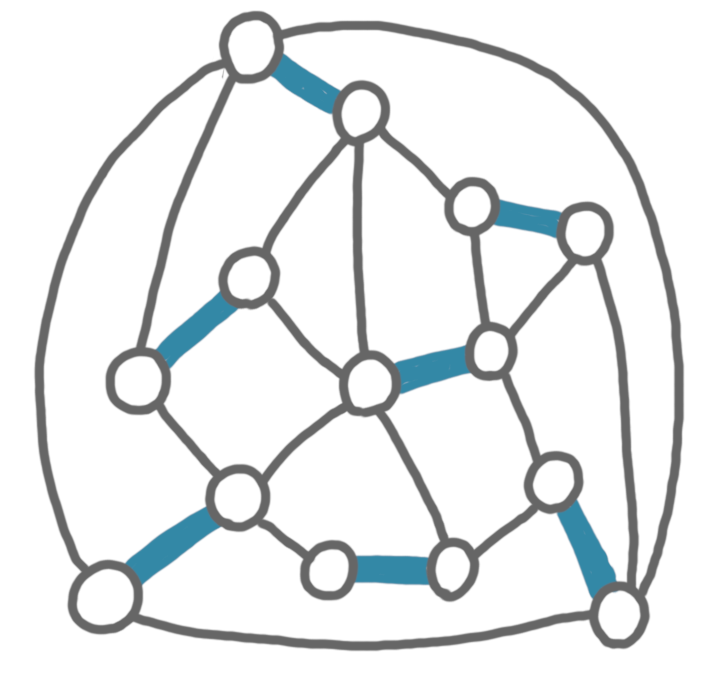

Consider the following planar graph (with a perfect matching highlighted for the sake of the explanation).

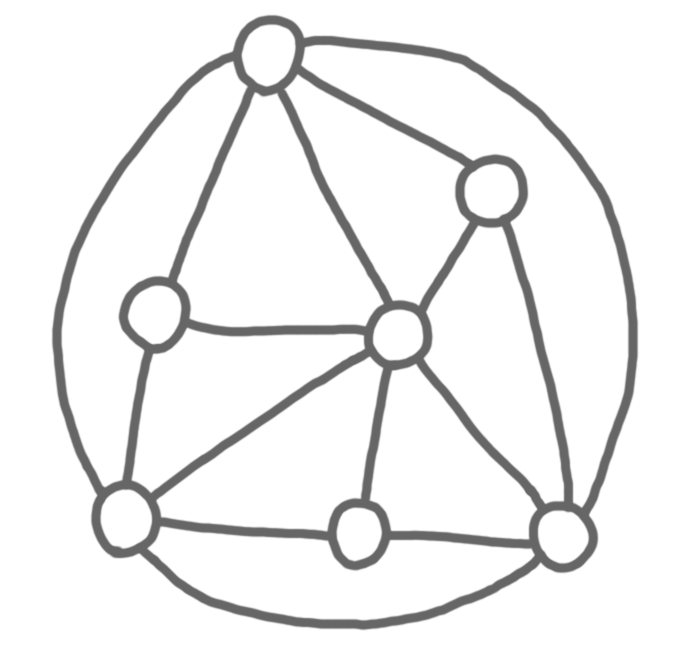

Now we contract the edges of the matching, keeping the adjcency if there was at least one egde linking the two pairs of nodes at hand. Because planarity is stable by contraction, the resulting graph is also planar.

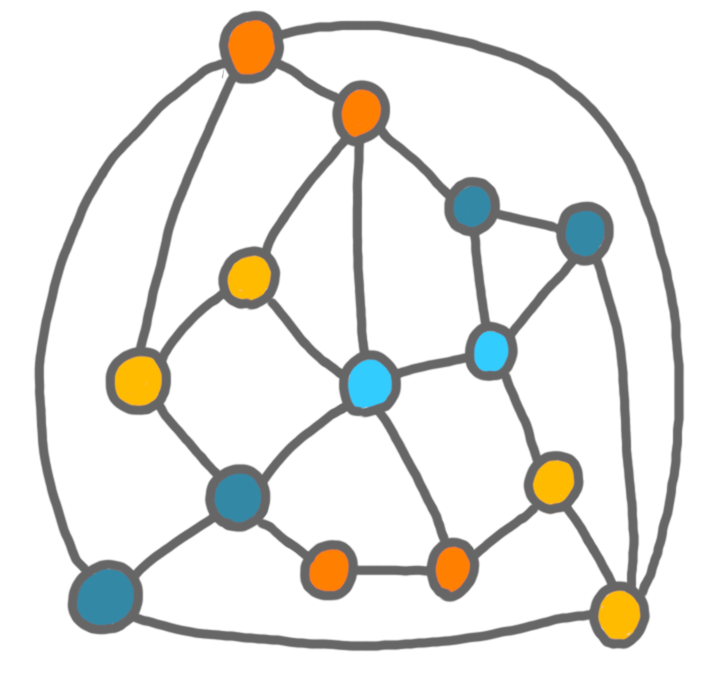

By the four color theorem, there exists a proper coloring of this new graph with at most four colors.

We use this coloring for our certification in the original graph: every node is given the color of its contracted node.

Because this was a proper coloring in the new graph, there is exactly one node with the same color in the neighborhood: the one it is matched to in the perfect matching. It is easy to check that this is a correct certification, and it uses only four different certificates, hence two bits.