March notes II.

09 Apr 2019Second set of notes for March 2019.

A pair of distributed computing talks

We had a couple of distributed computing talks this month. Here are a few words about the concepts involved.

Beeping model

The beeping model is a very weak model of distributed network computing. In this model, the nodes of the network communicate by beeping. At each round, a node decides to beep or not. And a node can receive only one information: either someone in the neighborhood has beeped, or not. One cannot know how many nodes beeped. In particular, if the node chooses to beep, then it cannot know if another node has beeped.

The beeping is used to model primitive communication, for example between cells. The surprising point is that you can actually do things in this model ! For example compute a maximal independent set (see this paper).

Superimposed codes

Beeps are binary information, thus to transmit more than one bit, nodes have to encode information into sequences of beeps. The problem is that a node may receive beeps from several neighbors, and a priori cannot know if beeps it heard form a single sequence, or if it is a mix of several sequences.

A nice tool to solve that is superimposed codes: these codes are such that if one superimpose them (that is, perform a bit-wise OR), one can still decode the different words. In other words any sequence can be decomposed uniquely into several code words.

It seems that these codes were already used for punched-cards…

Fixing blocking edges in stable marriage

A marriage (or bipartite matching) is a matching in a balanced bipartite graph, where every node is has a preference list. It is stable if not two participants would prefer to be matched together instead of their current matching (such a pair is called a blocking edge).

Gale and Shapley designed a well-known algorithm to compute such a marriage. But it starts from an empty solution. Suppose you want to start from a non-stable solution and improve it step by step, for example because you are designing a self-stabilizing algorithm. This is not easy.

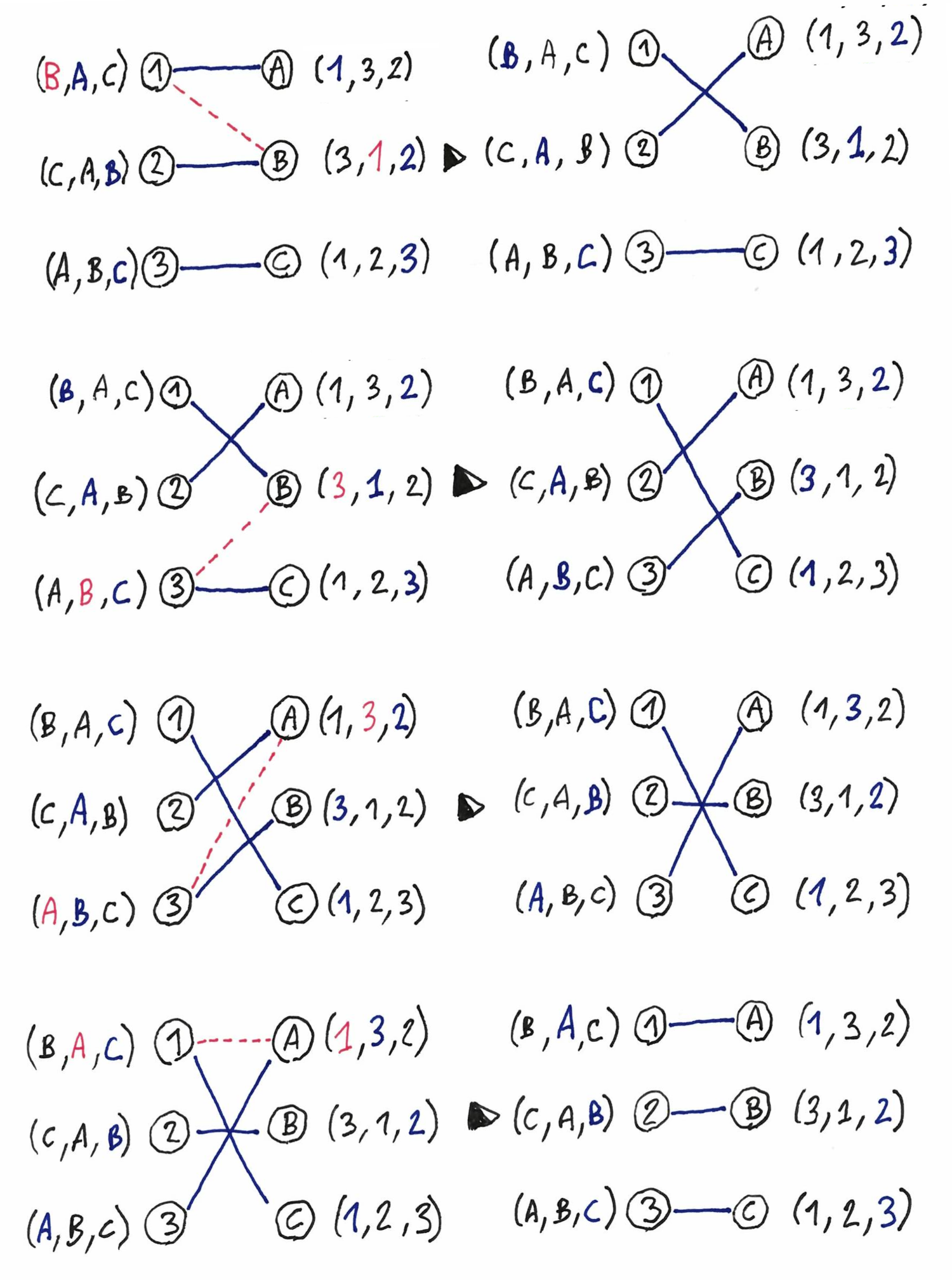

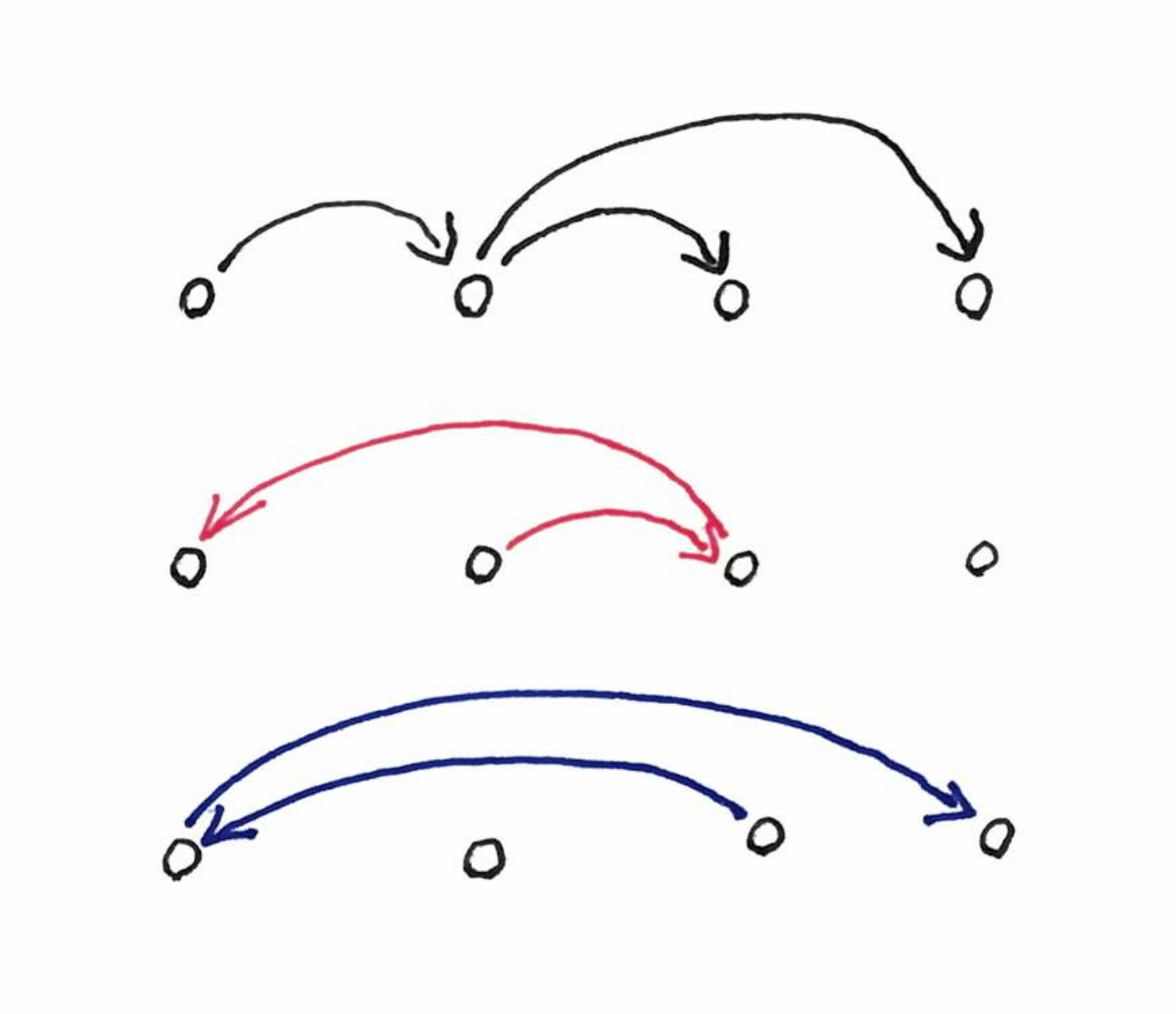

In the following example, attributed to Knuth, we start on the left from a solution that is unstable (the blocking pair is in red), and solve this pair on the right picture, and then iterate the procedure. Unfortunately, at the end of the procedure, we are back to the first instance!

Privacy in stable marriage

The classic centralized algorithms for stable marriage use the full list of preferences, that is there is no privacy for the participants. For distributed algorithms, it makes sense to try to minimize the amount of information the participants have to share to solve the task. For example the algorithm presented in the talk uses little information (e.g. “this player is already matched to someone higher in his/her list”).

[The talks were by Fabien Dufoulon and Marie Laveau, both PhD students in Paris-Sud University. Fabien told us about his new (not yet public) result in the beeping model, using a variant of superimposed codes. Marie told us about her result on self-stabilizing stable matching. It is this paper.]

Different techniques for different regimes (in rockets and algorithms)

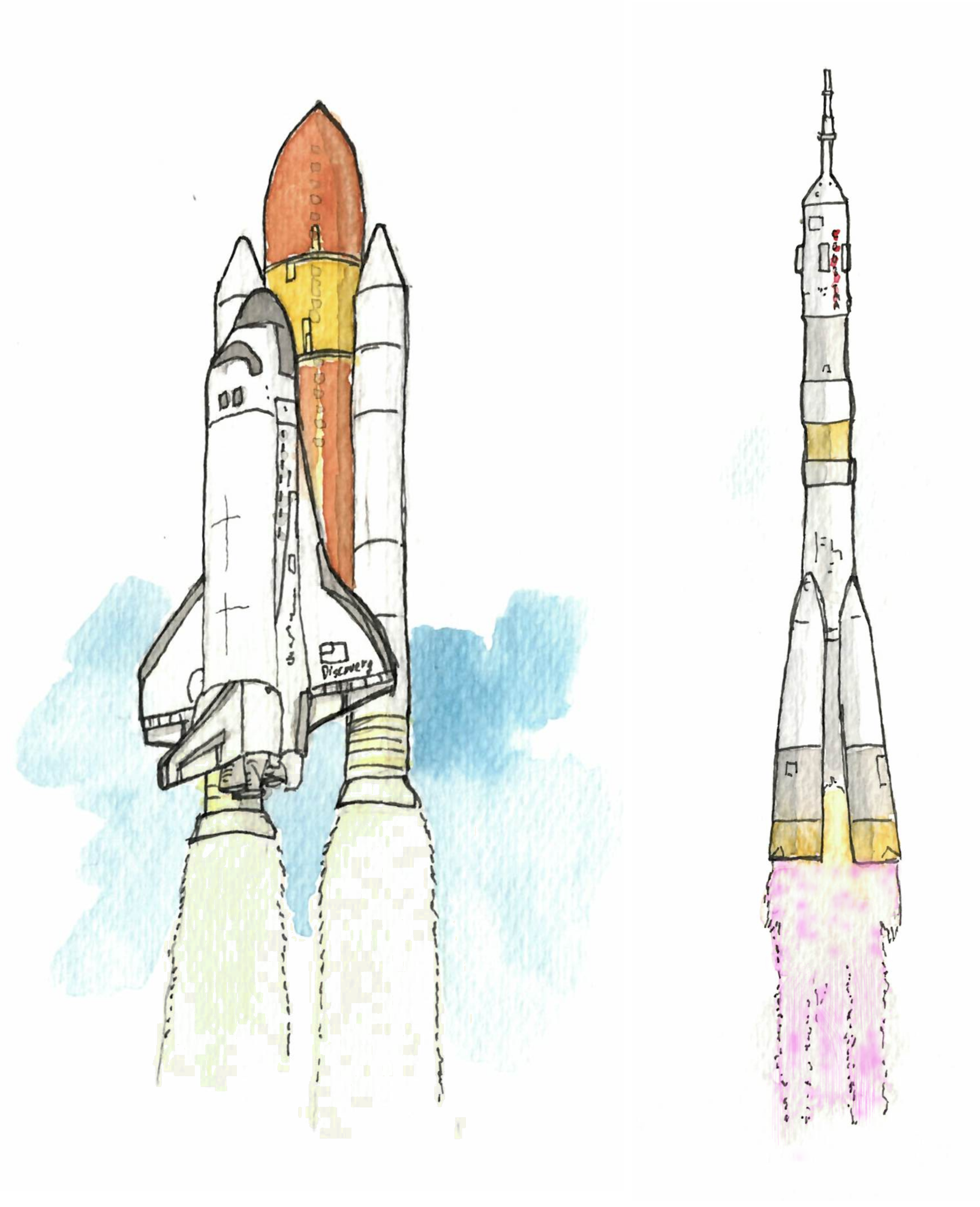

I discovered recently that the flames of different space rockets have different colors, partly because they use different mix of fuels.

Space shuttle (yellowish flames) and Soyouz (pinkish flames).

This was surprising to me, as I would naively think that there must be a solution that is considered “the best to push stuff upward”, and that everybody would use it.

But I guess different regimes (how much you want to lift, at which speed etc.) ask for different solutions. In the world of algorithms, it is similar to the following scenario. Say you want an algorithm for instances that depend on two parameters $n$ and $k$. Then you may use different technique for different regimes. For example, expressing $k$ as a function of $n$, you could have: for constant $k$ do brute-force, for logarithmic $k$ do some divide and conquer, for $k$ around $\sqrt{n}$ do dynamic programming, etc.

I wonder if we have such examples with many different regimes asking for many different solutions. In distributed graph algorithms, an example is coloring (and similar problems) where for bounded degree and unbounded degree you have completely different techniques.

For the related question of problems (with one parameter) having many different equally good solutions, I see $O(\log n)$-approximation of Set-Cover, for which you can basically use all the standard tools of approximation: greedy, LP-rounding, primal-dual etc.

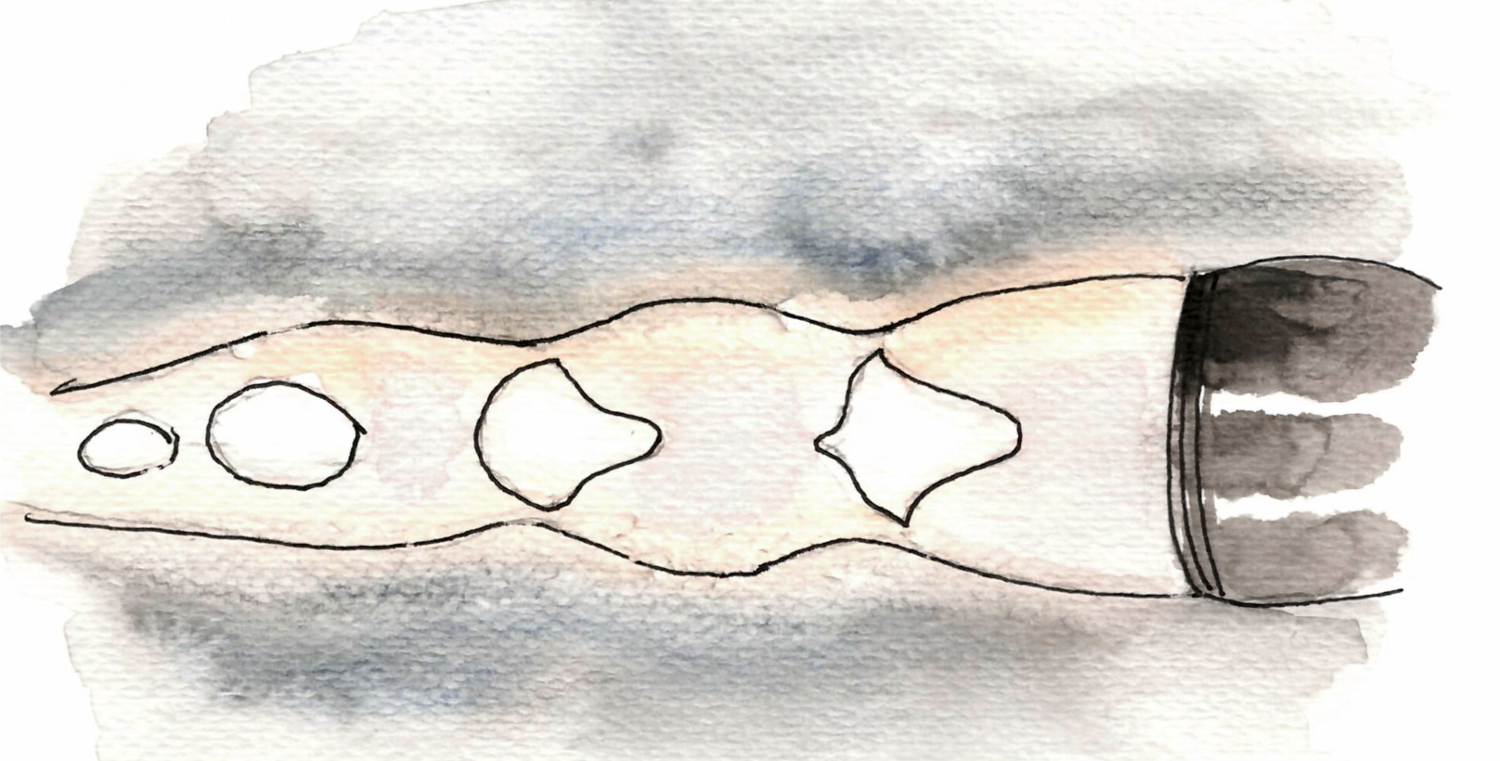

[I semi-randomly stumbled on this video (or more precisely the French-speaking version of it) that explains a lot of stuff about rockets flames. For example why one can see the kind of patterns below in rocket flames (it’s actually in the second part of the video).

These are called Mach disks or shock diamonds, and come from the fact that the flames expand when they get out of the engine, but because the outside pressure is higher, it is then recompressed, it heats up again, and then again expands etc. Maybe there is a discrete analogue for this too (convergence by oscillations?).]

Abel prize and limitations of the discrete approach

Lipton and Regan blog about the new Abel prize recipient, Karen Uhlenbeck, or actually about her research. They take the interesting approach of first trying to solve a problem with a discrete natural approach, and then to show how it fails, and how analysis in the style of Uhlenbeck’s research solves the problem.

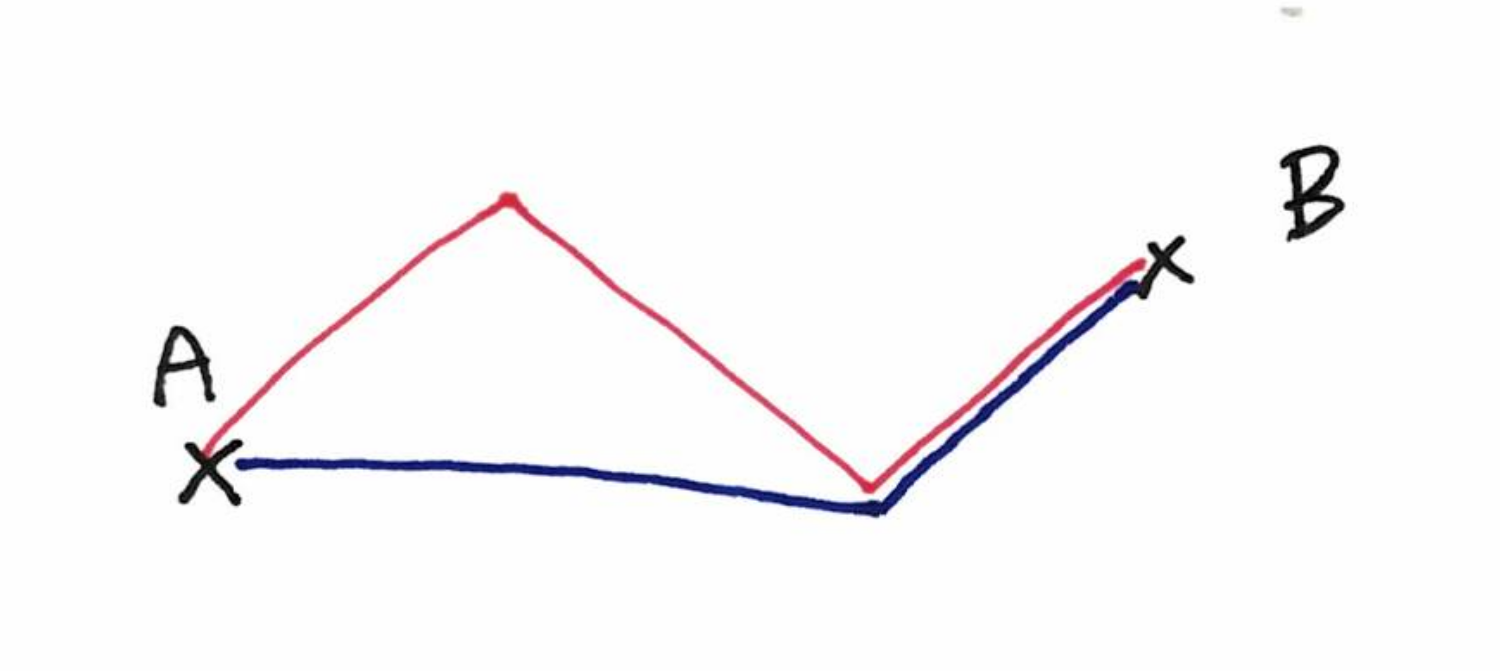

The question is simply to prove that in the plane the shortest path between two points is a straight line. The natural discrete approach is to consider polygonal lines, to prove the statement by induction (on the picture below the blue line is better by triangle inequality), and then to say “every curve is polygonal line up to small stuff”.

The reason why it fails is all the nasty functions (fractals and other monsters) that ruin the last step.

SIGACT news, year and conference reviews

I was surprised to receive SIGACT news at home, and then remembered than I had registered to ACM for FOCS. It is first time I glance at SIGACT news, as I don’t have access to it online.

I was especially interested in the online algorithm review. For the first issue of the year, the author, Rob van Stee, does a review of the key results of 2018 in his area. This is very nice format, that gives a higher perspective on a field.

A more classic format is the review of a conference. In my experience, this is less useful, because (1) one cannot be knowledgeable about every topic in a conference, (2) one tries to be quite exhaustive ; consequently the review often ends up being a list of small, not very informative sentences about many many papers.

[By the way, it’s sad that SIGACT News is not open-access.]

1point5 and conference travel

Le Monde, one of the major French newpapers, published the letter of the “1point5” group. This name comes from the objective of keeping global warming upper bounded by 1.5 degree Celsius. The collective is interested in the impact of research on climate. They basically argue that research should be made differently to reduce its impact on the planet.

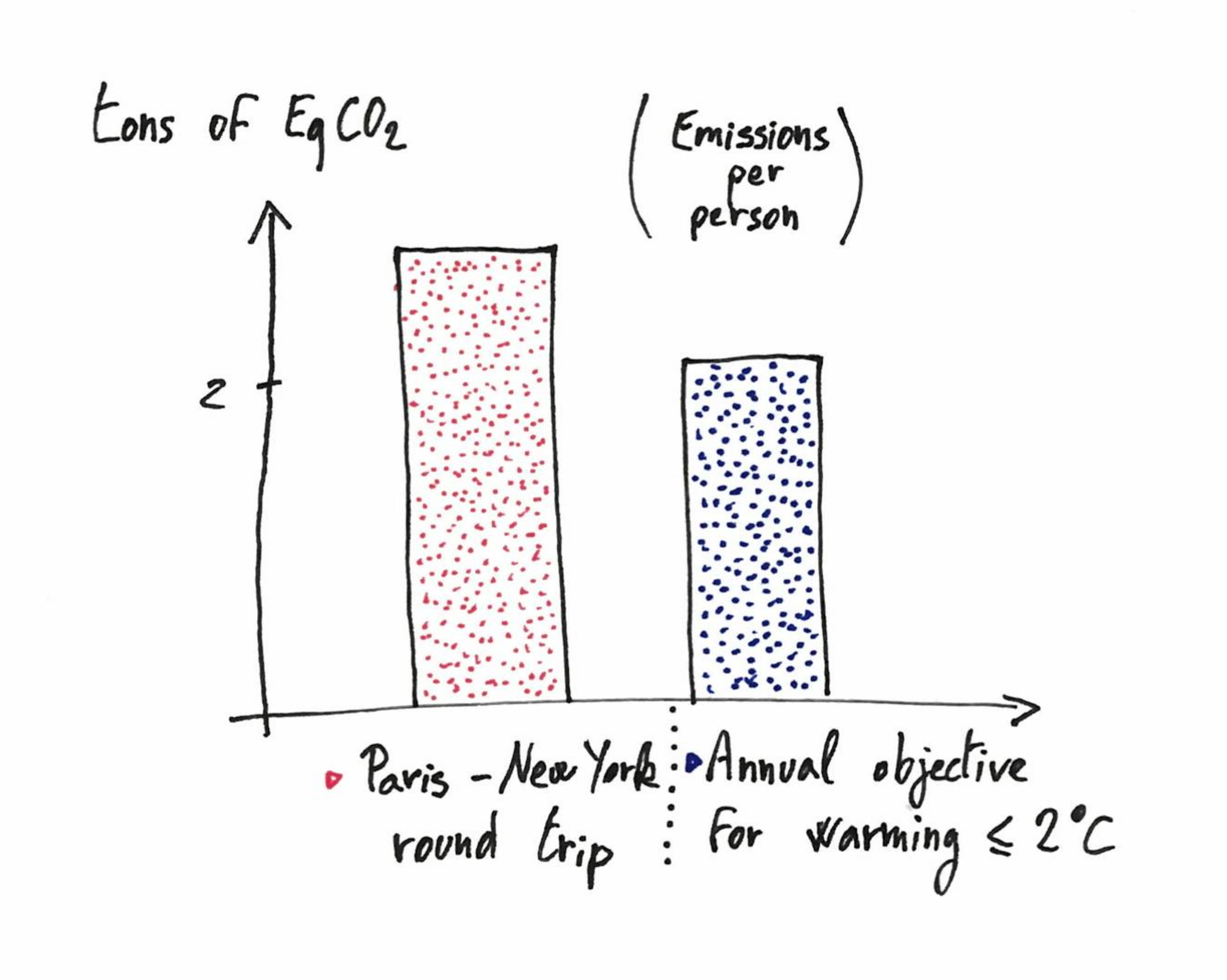

I have been thinking about this for a while. It happened to me several times to go to a conference, and think it was not worth the kerosene. Conferences are often nice moments, you indeed learn stuff and make new projects, but it’s difficult to argue that this is as convincing as the following picture.

The precise numbers can be discussed, but I got them from very reliable sources, and everywhere you will find numbers in the same ballpark.

In the long term, we can hope to make conferences less numerous, more efficient, more local. But in the short, term it seems that the only solution is to avoid submitting to far away conferences. Obviously this is a very broad topic…

Place in a queue

I recently went to a doctor who does not take appointments, thus people wait. The rule is “first-in first-cured” and people have to remember when it’s their turn. It is usually fine, but sometimes, maybe by mistake, maybe by slyness, people disagree. I noticed that people in the room have somehow random sampling of the order, e.g. “I arrived before this person, that person was here before, these two I don’t know”.

You get diagrams like this one (with some inconsistencies):

Making this into a linear order has a feedback-arcset flavor.

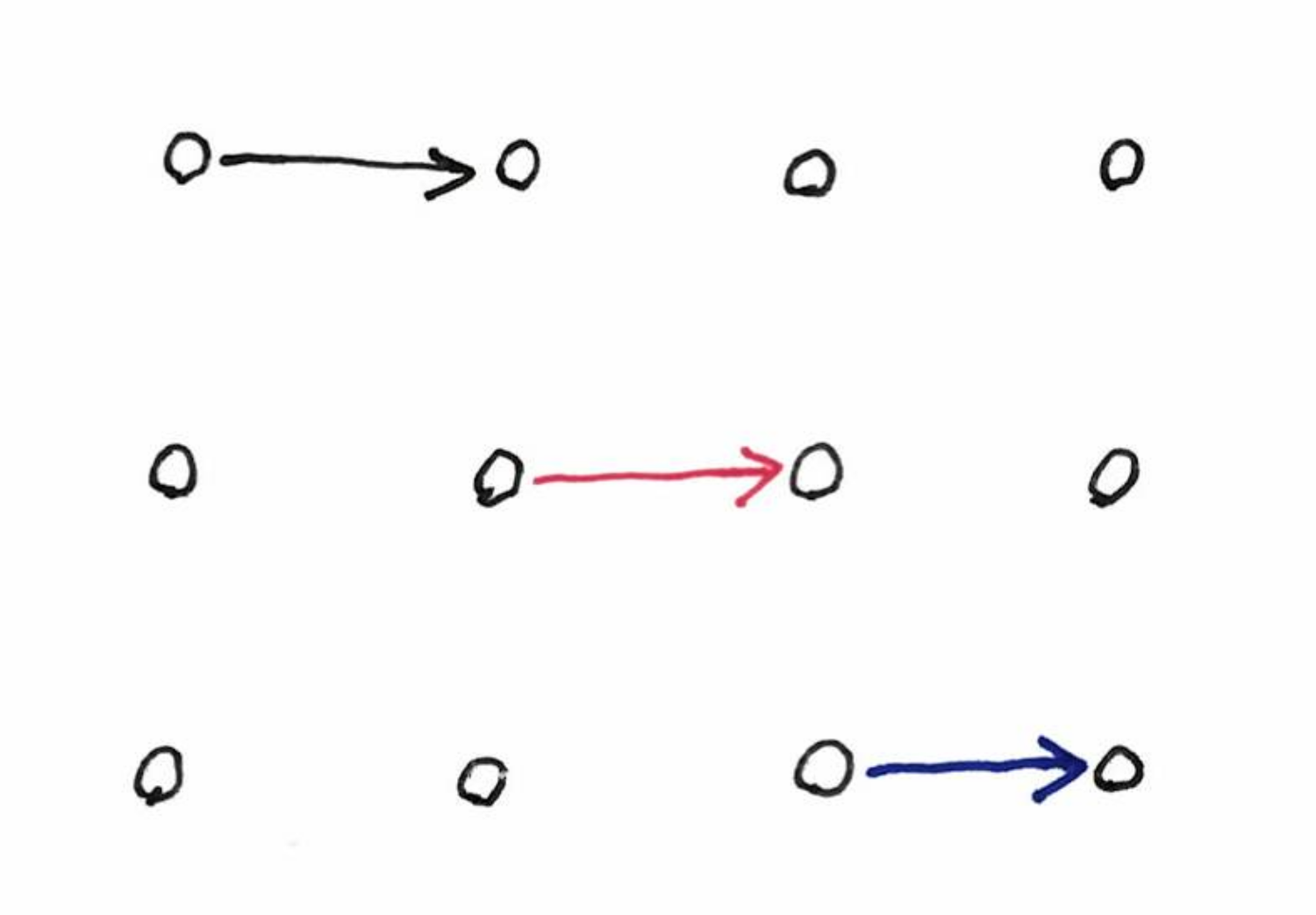

In other countries, I noticed that people, when they arrive say to a restaurant, ask “who is the latest arrived?”, which gives a simpler picture:

But maybe it’s less robust to slyness..?