Notes for February 21

25 Feb 2021Some February notes. As usual I have a growing backlog of topics I want to write about, so this is not very new stuff.

A picture from February 2021.

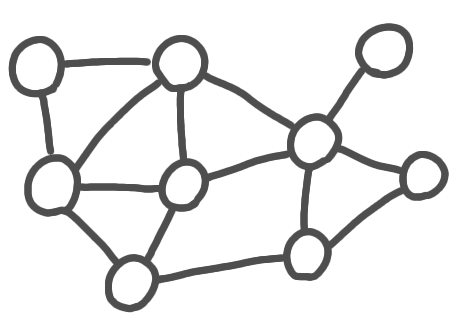

Karp-Sipser algorithm and simple algorithms

Simple algorithms, even when they do not achieve state-of-the-art performance or precision, are precious. As the call for paper of SOSA states: “The benefits of simplicity are manifold: simpler algorithms manifest a better understanding of the problem at hand; they are more likely to be implemented and trusted by practitioners; they can serve as benchmarks, as an initialization step, or as the basis for a “state of the art’’ algorithm; they are more easily taught and are more likely to be included in algorithms textbooks; and they attract a broader set of researchers to difficult algorithmic problems.”

I came across Karp-Sipser algorithm while working on kidney exchange with José Correa and his master student Guillermo Dinamarca. It is a very simple matching algorithm with surprizingly good performance. The basic version is the following:

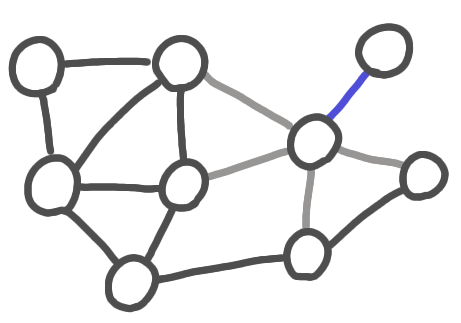

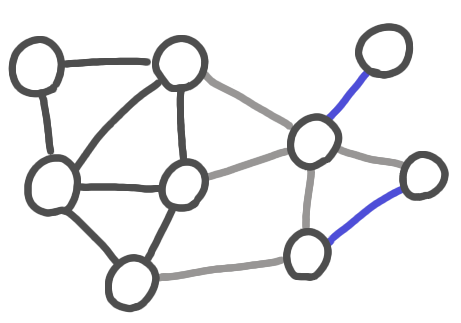

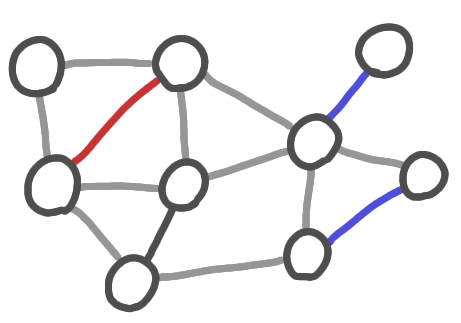

Iterate:

1. If there are pendent edges, take one at random,

add it to the matching, remove the nodes from the graph.

2. Otherwise take an edge at random,

add it to the matching, remove the nodes from the graph.

|

|

|

|

|

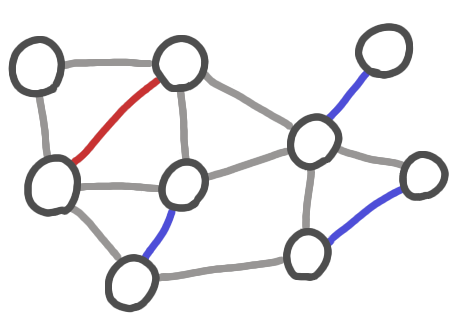

A run of Karp-Sipser algorithm. The blue edges are taken using the first rule. The red edge is taken using the second rule. The grey edges are the edges that that removed.

There exists a slightly more complicated version (as detailed in this blog post), but let’s focus on this one.

Consider a (sparse) Erdos-Renyi random graph, with $cn/2$ edges. It is proved in this paper, that refines the original one that:

- If $c< e $, then Karp-Sipser algorithm finds a maximum matching with high probability (!).

- If $c > e$, then with high probability Karp-Sipser algorithm finds a $O(n^{1/5+o(1)})$ approximation of the maximum matching.

The sharp threshold at $e$ is surprising at first, but actually such thresholds often appear in topics related to random graphs. Note that the even simpler algorithm that just takes edges at random does not achieve such a good result.

The algorithm also performs very well in practice, see the blog post mentioned above.

Making surveys more accurate via mechanism design

I am sometimes a bit suspicious about some results in say medecine or sociology, that are based on surveys. There is an obvious bias: only people willing to answer such surveys appear in the result.

This is an issue only if there is a correlation between the willingness to answer the survey and the topic of the survey. But such correlation can appear pretty easily. For example in a survey about the people weights, a person who is happy with his/her weight might be more willing to answer. This is the starting point of a not so recent post on the blog Theory Dish.

The blog details several approaches to design a mechanism that would allow to get an unbiased sample. These mechanisms are based on paying the individuals for their data. Different people would give different prices to their data, and one would like to pay the right price for each person. To do so the mechanisms basically ask the price for each individual, and then use a probabilistic process to decide whether to make an offer or not, and to decide the amount of the offer.

Once the problem is defined in a mathematical way, one can try to optimize the mechanism, minimizing the variance etc.

About distinguishing some papers in a conference

There is a trend in conferences to distinguish some papers from the others. In the conferences I go to, this takes of form of best papers awards and of invitation to journals special issues. I saw in the call for paper of LICS 2021 that another distinction was introduced:

“Starting in 2021, around 10% of accepted LICS papers will be selected as distinguished papers. These are papers that, in the view of the LICS program committee, make exceptionally strong contribution to the field and should be read by a broad audience due their relevance, originality, significance and clarity.”

Also, I think that large machine learning conferences use various such “levels” for papers, like poster presentation, oral presentation, etc.

I don’t know what to think about this. One the one hand one would like to have all conference participants on the same level, to insure a friendly egalitarian atmosphere, and avoid one more layer of competition in the publication process. On the other hand, having more levels allows to give a finer note to a paper, avoiding the pretty random threshold of “it is accepted thus a really good paper” versus “it is not accepted, thus is not at the level of the conference”.

Feedback about teaching online

Jukka Suomela has a very useful post about his experience in online teaching.

The course taught is in a format that is not very common in France: 6 weeks, with an expected student workload of 20+ hours/week. This allowed Jukka and his team to have a very active slack channel, which probably made students feel more involved, and more connected to each other. (The student feedback on the course was excellent.)

The students had access to brief recorded lectures of very high quality (you can find them online). The text of these lectures was written in advance, and the sound and image quality is well above the average. The short format and the quality help to stay focused, which is usually hard in remote teaching.

Jukka also used a script for his SWAT 2020 keynote talk, you can find the video of the talk here and the script here. Without going all the way to exactly reading a script, I guess that writing a text that goes with a set of slides makes things clearer in the speaker’s mind. Actually for their first lectures, the lecturers at Collège de France (a prestigious French research institution) are advised to do exactly that: write the text of the lecture in advance.

[EDIT: there used to be a drawing here to finish the post. It has been moved to a separate post.]